WOULD YOU REWRITE LIKE HEMINGWAY DAILY?

If you think genius is effortless, read to the end. Hemingway’s masterpiece was not born in inspiration—it was carved in pain, discipline, and relentless daily rewrites. Could you endure his grind?

You'll want to read to the end.

This isn't just a story about Ernest Hemingway—it's a lesson on how masterpieces are truly forged.

DAWN RITUAL: REWRITING YESTERDAY

In the merciless winter of 1950, Ernest Hemingway forged a ruthless daily ritual at Finca Vigía, his battered sanctuary in Cuba. No grand desk awaited him—instead, he claimed a single square foot atop a cluttered bookcase. He stood to write, typewriter chest-high on a wooden plank, pencils and unyielding resolve within grasp.

Comfort played no part. Necessity dictated the stance. Standing kept his spine from pain, his mind sharp as steel. Each dawn he revisited every line from yesterday—not to admire, but to dismantle and reconstruct.

“I always rewrite each day up to the point where I stopped.”

– Ernest Hemingway

He carved yesterday’s prose until it drew blood. Only then would he advance. This was not gentle refinement; it was the relentless grind, the engine powering each day's momentum.

“You read what you have written… and as you always stop when you know what is going to happen next, you go on from there.”

– Ernest Hemingway

Every sunrise was a calculated reset: honing yesterday, fueling tomorrow. His discipline was ironclad, commencing precisely at six, ceasing at noon, irrespective of triumph or torment.

This embodies the McCallian Law of the Daily Chisel: True mastery emerges slowly, carved through ruthless repetition and uncompromising standards.

Hemingway did not polish—he forged. Each morning, he sharpened his narrative with a craftsman's precision and a warrior’s hunger.

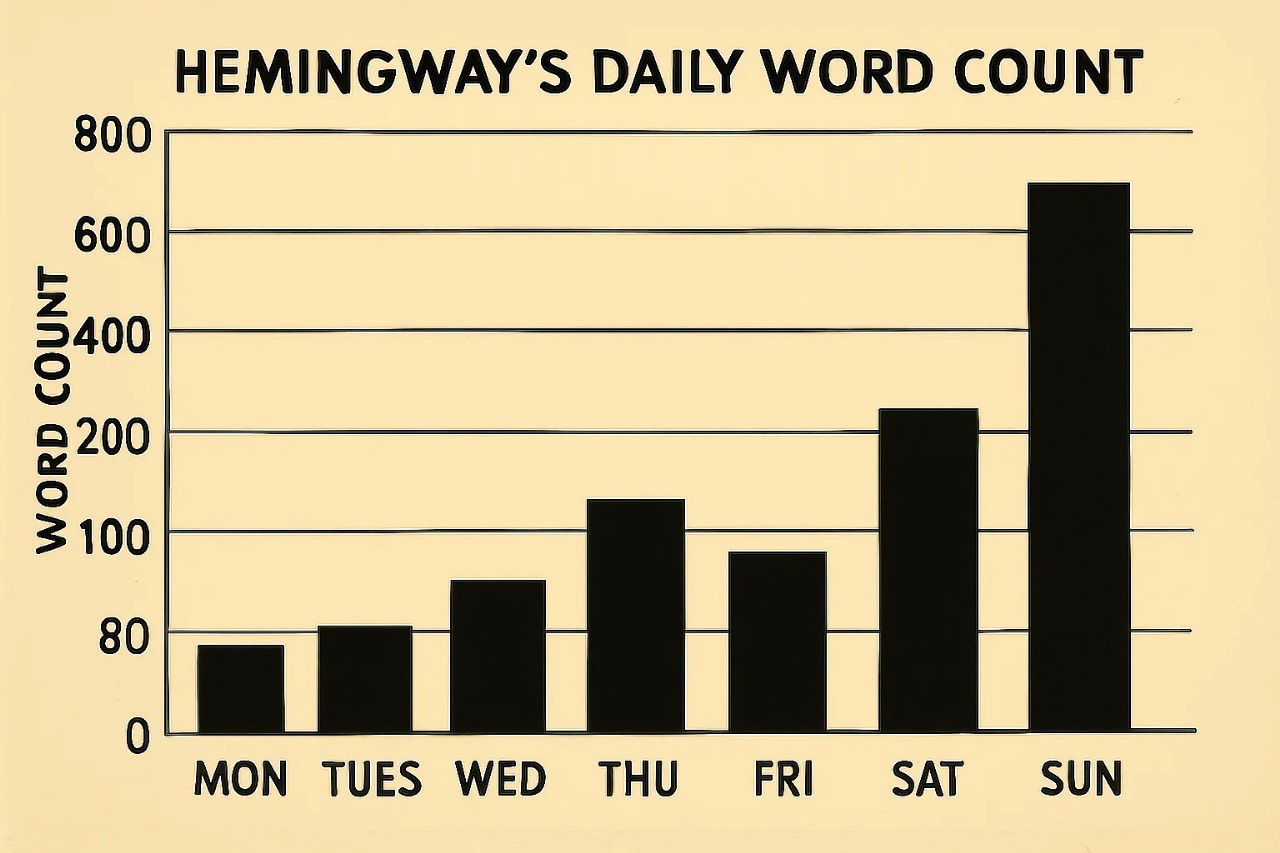

THE RELENTLESS ROUTINE: "DAILY CHISEL" IN ACTION

Hemingway’s regimen during "The Old Man and the Sea" was unyielding in its rigor. At first light, the quiet Cuban dawn found him rigid as a monk, shifting only slightly from foot to foot, utterly consumed by his craft.

Observers noted his absolute concentration, oblivious to oppressive heat, sweat dripping unnoticed as pages multiplied. Inspired days brought childlike zeal; frustration ushered in restlessness and irritation. Yet neither triumph nor despair could alter his course. Hemingway stopped mid-sentence intentionally, always leaving himself hungry for more.

"You write until you come to a place where you still have your juice and know what will happen next, and you stop. It is the wait until the next day that is hard."

– Ernest Hemingway

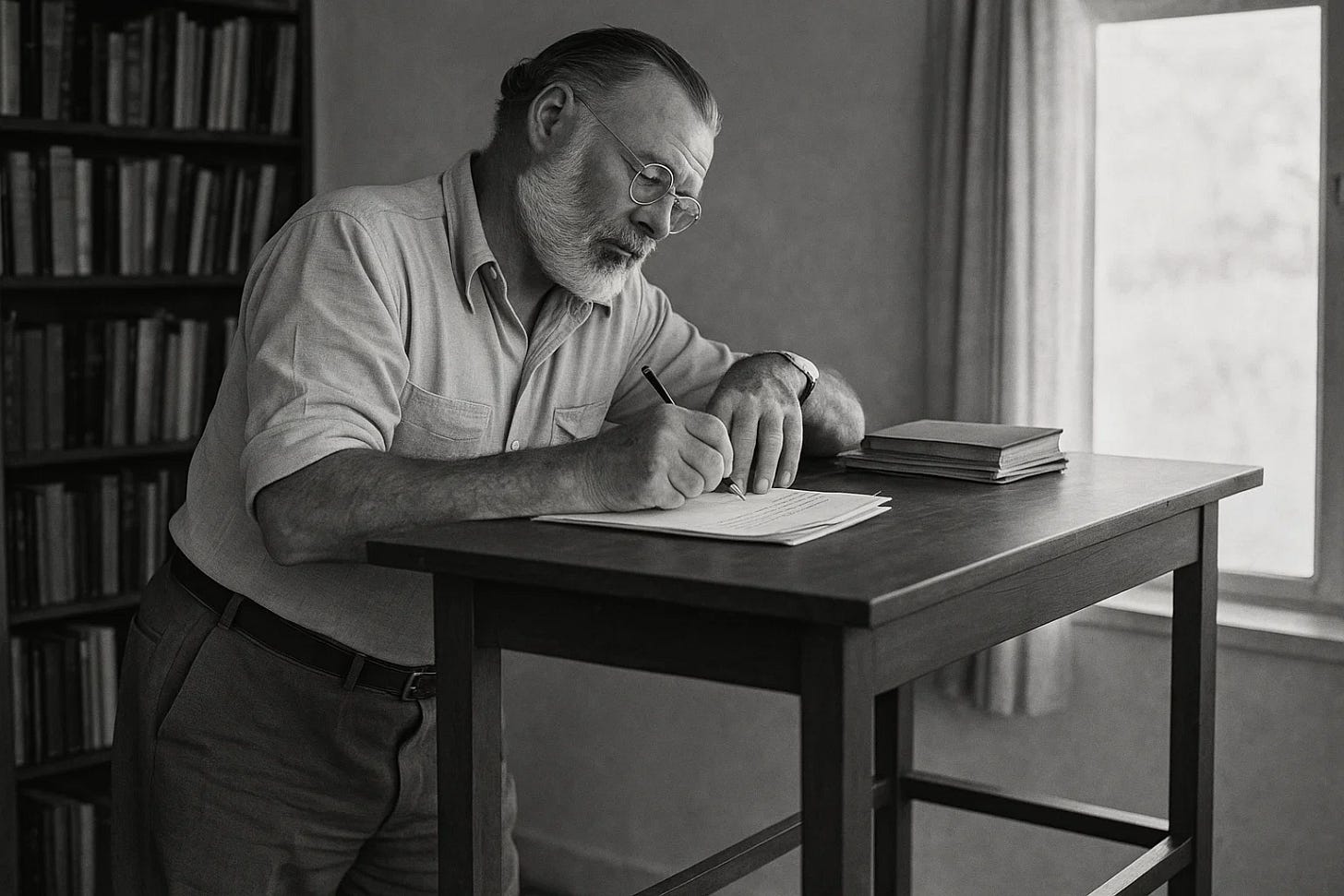

This calculated pause bred urgency, transforming dread into addiction. Each dawn brought another chance—another opportunity to refine, another step towards perfection. Hemingway meticulously recorded his daily word counts—450, 575, 462, 1250—each figure testament to relentless advancement. Successful days rewarded him with guilt-free afternoons for fishing or rest, but each morning demanded new proof of incremental growth.

His friend A.E. Hotchner observed Hemingway carefully weighing every word. Endings underwent dozens of rewrites.

"The only kind of writing is rewriting. The first draft of anything is trash."

– Ernest Hemingway

Hemingway understood that greatness was not spontaneous—it was hammered from persistent effort.

While crafting "The Old Man and the Sea," he pushed to a swift thousand words per day, yet each line endured obsessive refinement. If the morning’s labor left him drained, it was the fulfilling exhaustion known only to those who have truly given their all.

“Empty, and at the same time never empty but filling, as when you have made love to someone you love."

–Ernest Hemingway

Each session concluded depleted yet deeply satisfied, prepared to rise once more at dawn to resume chiseling.

Every day marked incremental progress—a masterpiece patiently shaped by relentless hands.

FRUSTRATION, DISCIPLINE, AND A BIT OF MAGIC

Hemingway’s daily grind was brutal. Mornings came when each sentence felt like fighting through mud. Some days, he wrestled with a single paragraph, muttering curses under his breath when words failed him. Biographers recall him pacing restlessly, staring through windows, then returning to battle the typewriter once more.

He enforced strict discipline: no drinks until the day’s writing was finished—a considerable act of restraint for a man who enjoyed his daiquiris. His wife, Mary Welsh Hemingway, watched these daily rituals unfold with a mixture of admiration and frustration. Their marriage was strained, yet during those intense weeks, Mary saw something remarkable happening. Each evening, Hemingway handed her pages fresh from the typewriter. She read while he stepped away to clear his mind, perhaps fishing or responding to letters.

Mary was consistently moved by the unfolding story. The simple fisherman’s tale was born from struggle and frustration, yet each night’s draft emerged clearer, stronger. It touched her profoundly, prompting her to admit later that it made her ready to forgive all Hemingway’s faults and failings during that time. She sensed the presence of something special, a quiet magic behind the relentless effort.

Hemingway himself recognized it. Despite the crippling self-doubt common to all writers, he felt a rare certainty about this work. On good days, he emerged from his room exhilarated. George Plimpton, who interviewed Hemingway for the Paris Review, recalled him leaving for his midday swim "excited as a boy," the morning’s pain replaced by glowing satisfaction.

Friends and colleagues noticed Hemingway was unusually obsessed with his protagonist, Santiago, treating him like a living friend rather than a fictional character. Wallace Meyer, his editor, described Hemingway as almost "possessed" by the story. Yet this possession never diluted his discipline.

Even after completing the manuscript swiftly—in just six weeks—he refused to rush it into print. Instead, he meticulously refined each sentence, debating whether it should stand alone or remain part of a larger narrative.

In the end, Hemingway trusted his chiseling instinct. He made small, deliberate refinements until he knew he had carved something worthy. Only when the work met his rigorous standards did he finally let go.

TRIUMPH FORGED BY DAILY REWRITING

When Hemingway sent The Old Man and the Sea to his publisher, he did so with unusual certainty. To editor Wallace Meyer, he declared simply, "I know that it is the best I can write ever for all of my life." This was no exaggeration. It was the conviction born from relentless rewriting, from shaping each sentence until it rang true.

He added that this novella was so powerful it "destroys any good and able work placed alongside it." For Hemingway, it was also a strike back—a clear response to those who claimed he was finished.

The result of Hemingway’s meticulous daily chisel was undeniable. Published in Life magazine in September 1952, the novella sold over five million copies in just two days. Critics who had torn apart his previous novel were stunned.

Time called it a masterpiece, while Hemingway’s old rival, William Faulkner, generously declared it "possibly the best single piece of any of us." In 1953, it won the Pulitzer Prize. The following year, Hemingway received the Nobel Prize for Literature.

Yet accolades were secondary to the deeper victory. Hemingway had proven something vital, most importantly to himself: through disciplined daily effort, he could still craft work that stood with his finest.

The Law of the Daily Chisel lives vividly in Hemingway’s process. Great stories are rarely sudden bursts of genius; more often, they're painstakingly crafted day by day, sentence by sentence. We see Hemingway at dawn, a solitary craftsman at his makeshift desk, refining yesterday’s lines, grinding through revisions until each sentence matched his inner vision. We witness the frustration of endless rewrites, and the quiet joy when a paragraph finally clicks into place.

The Old Man and the Sea itself mirrors Hemingway’s method. Santiago’s patient battle with the marlin echoes Hemingway’s patient battle with his prose. Santiago declares, "A man is not made for defeat," and neither was Hemingway. His friend A.E. Hotchner noted that the novella was Hemingway’s "counterattack" against doubt, proof that his talent was still sharp despite critics having dismissed him.

What drove Hemingway wasn’t genius alone, but relentless discipline: writing, revising, rewriting—every single day. He carved his masterpiece not in sweeping strokes, but through the cumulative force of incremental effort. Each dawn he rose, stood at his chest-high desk, and began chiseling again.

Through this steady, relentless rhythm, Hemingway transformed daily labor into timeless art, proving greatness is built not through moments, but habits—persistent, disciplined, and relentless.

JOIN THE TABLE: SHARE YOUR STORY

What's your "daily chisel"—the routine that keeps you going when writing is tough? Comment below and share your struggles or strategies. Every voice helps others stay in the fight.